Welcome to Blue Book!

Are you ready to join the thousands of companies who rely on Blue Book to drive smarter decisions? View our plans and get started today!

Still have questions? We’d love to show you what Blue Book can do for you. Drop us a line– we’ve been waiting for you.

In this article

Temperature control is a big deal where fresh produce is concerned.

When the trailer doors are closed on a shipment of produce, it will sleep comfortably at proper storage temperatures. But when temperatures are too warm, it suffers through the night in a sweat.

Receivers, of course, want to discover well-rested product when the trailer doors are opened. Product with dark circles under its eyes often gets rejected.

And when product is rejected or received under protest due to a loss of temperature control, fingers naturally start pointing at the carrier.

Carriers, however, undeterred by the prospect of an uphill fight, often respond by blaming the loss of temperature control on warm pulp temperatures at loading.

It’s an argument we hear a lot. So, for this article, we wanted to put together a list of considerations Blue Book works through when assessing these disputes.

Carriers: Not Responsible for Reducing Pulp Temperatures

As a starting point, it’s important to note that carriers are responsible for maintaining air temperature control in the trailer while the product is in their possession. Carriers are not responsible for reducing pulp temperatures.

As explained in Section (6.4) of our Transportation Guidelines: “A Carrier’s reefer system is not responsible for lowering pulp temperatures. Warm pulp temperatures at destination do not necessarily indicate a breach of contract by the Carrier because warm pulp temperatures at destination could result from a shipper’s failure to properly precool produce prior to loading.

“Pulp temperatures at destination, however, may be some evidence of temperatures within the trailer during the haul, particularly when the pulp temperatures at loading are well-documented.”

So, if a shipment of lettuce is picked up and delivered at 38°F, we would not recognize the destination pulp temperatures as a proper basis for a carrier claim. Carriers are not an extension of the shipper’s quality assurance team—they are carriers.

If carriers properly protect the perishable product while it’s in their possession by maintaining air temperature control in the trailer, they are not responsible for the shipper’s failure to properly precool the product.

If carriers properly protect the perishable product while it’s in their possession by maintaining air temperature control in the trailer, they are not responsible for the shipper’s failure to properly precool the product.

Diligence on the Docks

The fact that carriers are not responsible for reducing the pulp temperatures, however, does not mean they shouldn’t be diligent on the shipping and receiving docks. When carriers sign for warm product with a “clean” bill of lading, they invite trouble.

When warm pulps are discovered and properly documented at destination, carriers find themselves playing defense—particularly when the bill of lading specifically indicates the product was pulping at, for example, 34°F, and the receiver notes pulps of 38°F on the proof of delivery.

On the face of it, this discrepancy suggests a loss of temperature control in transit.

And while it’s true carriers may be able to use readings from portable recorders and the reefer unit to show proper temperature control was maintained, a carrier’s failure to verify pulp temperatures at minimum forces it to defend against the claim.

What’s more, if the air temperature readings from the portable recorder or the reefer download are borderline, a discrepancy between the pulp temperatures documented at origin and those documented at destination may be enough to tip the scales against the carrier.

Not allowed to verify

If carriers are not permitted to verify pulps at the shipping facility, we generally recognize a carrier’s right to refuse the shipment. Alternatively, the carrier could sign the bill of lading “shipper’s load and count” or “no pulping permitted” to ensure the bill of lading cannot later be used against it as proof of pulp temperatures at origin.

When carriers throw caution to the wind and sign the bill of lading “clean,” this may later be interpreted to mean either: (1) the pulp temperatures were good; or (2) the carrier has no firsthand direct knowledge of warm pulp temperatures at loading and is merely speculating.

And even if the carrier’s speculations raise some doubt with respect to the pulp temperatures at origin, an arbitrator is likely to point out the carrier’s defense relies on uncertainty it had an opportunity to resolve before signing for the load.

Generally speaking, arbitrators don’t like to give the benefit of the doubt to a party that created or failed to resolve an uncertainty it later relies on to support its position.

Meanwhile, shippers can usually be expected to point to internal records and their direct knowledge (i.e., affidavits) of their precooling and loading procedures as evidence of proper precooling.

This type of evidence tends to be strong enough to make the shipper-claimant’s prima facie case and shift the burden of proof to the carrier to show “freedom from negligence” under the common law of common carriage.

Ultimately, the air temperature readings from portable and reefer-based recorders provide far more information about the air temperatures in transit than a piece of fruit ever could.

The Pattern of Temperature Readings

Ultimately, the air temperature readings from portable and reefer-based recorders provide far more information about the air temperatures in transit than a piece of fruit ever could.

Complicating matters somewhat, however, is the fact that warm product temperatures will affect the surrounding air temperatures in the trailer.

Taken to an extreme, a full truckload of very warm product could, in fact, cause freezing of the top layers of the rear pallets as the reefer unit blows colder and colder air trying to regulate the return air readings in the nose of the trailer.

In a less extreme scenario, when product is loaded warm, we typically expect to see warmer readings on the portable recorder during the first few hours of the trip, with temperatures normalizing as field heat dissipates and the rate of respiration slows (respiration rates generally slow within 24-hours after harvest).

This type of pattern to the air temperature readings can go a long way in support of a carrier’s denial of a claim.

Conversely, when temperature recorders indicate air temperatures were warm or increasing well into the trip, or were rising and falling with the outside temperatures, these patterns do little to help the carrier meet its burden of proving freedom from negligence and shipper error.

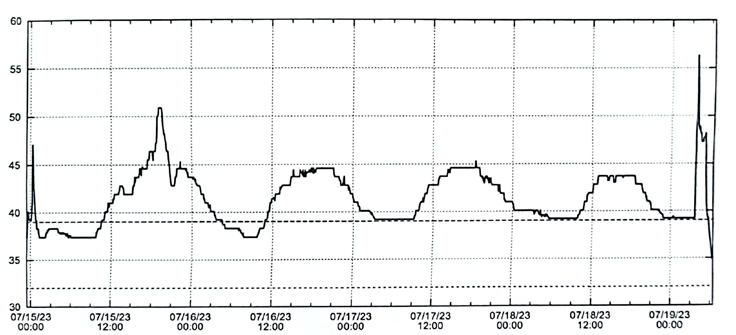

The readings below are from a portable temperature recorder placed with a shipment that was supposed to be maintained at 34°F. In response to a claim based on warm temperatures, the carrier claimed the product was loaded warm at shipping point.

Reviewing these readings, we see that air temperatures in the trailer stabilized between 36-37°F for close to 10 hours during the first morning.

Had temperatures remained in this range and normalized further during the later days of the trip, this initial temperature variance, in our view, would be consistent with a carrier’s suggestion the product was loaded warm, and that it was “free from negligence.”

As the trip progresses, however, we see the opposite. The readings began to climb over the next 10 hours to over 50°F—far beyond what would be considered a normal variance per our Transportation Guidelines.

Even product that was loaded warm gives off less heat over time and should not overwhelm a properly functioning reefer system (i.e., the reefer unit and a well-insulated trailer) in the later days of a long-haul trip.

The remainder of the trip shows a similar though less extreme pattern where the readings fluctuate significantly with the warmer readings occurring in the afternoon and evening hours, as if outside temperatures (rather than heat from the product) were driving the warm air temperatures in the trailer.

These readings are simply inconsistent with a carrier’s suggestion that the temperature control issues were caused by warm pulp temperatures at loading.

Even product that was loaded warm gives off less heat over time and should not overwhelm a properly functioning reefer system (i.e., the reefer unit and a well-insulated trailer) in the later days of a long-haul trip.

How Warm was this Allegedly Warm Product Anyway?

If temperatures in the trailer were supposed to be maintained at 34°F, and temperature readings in the mid-40s were recorded, we have to wonder, just how warm the product would have to be to outmuscle a properly functioning reefer system operating within a properly insulated trailer.

Was this product really pulping at 60°F? Barring some unusual circumstances, this seems highly unlikely. Surely the shipper is going to be able to make a credible case for having done a better job precooling its product.

And if the product was pulping at, say, 40°F, even 45°F, could product at these temperatures really be to blame for air temperatures in the 40s? A properly functioning reefer system coupled with a well-insulated trailer would not be so completely overwhelmed by product pulping at these temperatures.

Conclusion

Temperature claims must be carefully considered on a case-by-case basis. There’s no easy way to make quick work of them.

But hopefully the considerations discussed in this article will help give some framework to assessments. As always, your feedback is welcome at tradingassist@bluebookservices.com.